Making Regeneration Regenerative

This is the second article in the series exploring how masterplans and regeneration schemes should evolve to be more exciting and deliver for people and the planet.

Previously, we discussed how masterplans must integrate social, economic, and environmental considerations from the outset of the design process to achieve genuine success. This is fundamental to ensure spatial proposals align with the social needs of local communities while respecting the planet’s boundaries—and should absolutely be the way we should think about urban regeneration from now on.

Without this underlying mindset, designs risk a blank slate approach, where a new urban form is seen as the only possible solution for a thriving place. Unnecessary demolitions can become inevitable, ultimately reinforcing the narrative that a building’s value is restricted exclusively to its current state and performance. If, on the other hand, we start with what we already have, we can deliver genuinely regenerative places that can adapt and evolve rather than aim for abrupt and definitive change.

The current energy and cost of living crises have brought retrofitting to the forefront of discussions in place based strategies. With over 3.3m UK households, or 11%, in fuel poverty, almost one million homes in the UK suffering from severe dampness, and considering that 80% of the homes that will exist in 2050 already have been built, the need for retrofits is both a quality of life issue and a moral imperative.

The quality of existing commercial buildings is also far from optimal. ‘Across London, approximately 92m sq ft of office space has an EPC rating below grade C, over half of total office floorspace’. These buildings not only require intervention to reduce their carbon footprint, but could also become unlettable under the upcoming changes in energy performance regulations.

If we hope to achieve net zero by 2050, retrofitting must become the default way of delivering new spaces. And it needs to happen now.

Integrated approach

Much recent focus has been on transitioning to renewable energy and energy efficiency—in other words, reducing operational carbon. This has created a mentality that retrofits can’t achieve high levels of efficiency and, as long as a new building is energy efficient, its remaining carbon impact is acceptable. However, that’s only part of the equation. Embodied carbon (emissions associated with materials and construction processes) need to be given more consideration if we are to maximise our reduction in carbon impact. Embodied carbon is responsible for roughly 20% of built environment emissions and will account for more than half of all emissions by 2035.

To reduce the predilection of building new, we need to better and more specifically define optimal retrofit levels for assets. LETI suggests a 70% reduction in energy consumption is where the balance between social and environmental benefits and delivery costs lies. Implementing this on a large scale could result in a significant reduction in the overall operational carbon emissions of the building stock without the need to rebuild from scratch. In addition, we should explore creative design solutions that retain at least the super- and sub-structures of a building, which account for roughly 65% of its embodied carbon. Saving existing structures can prevent tonnes of carbon emissions and raw material extraction, avoiding resource depletion and degradation. Material efficiency, low-carbon materials, and intensifying the use of existing buildings should also be considered. In the span of 5 years, the retrofit of 750,000 London homes could be funded by the savings of using materials better and avoiding new construction.

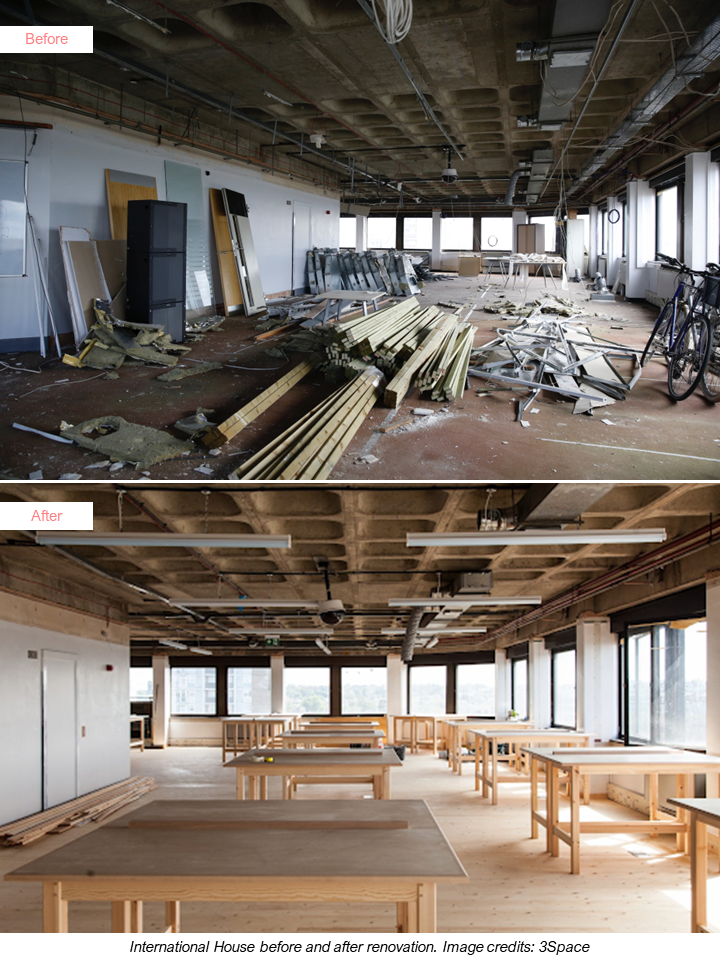

A fantastic example of building repurposing is International House, a council-owned office in Brixton, which at 6000m2 spread over 12 storeys is one of London’s largest affordable workspaces.

Until 2018, International House was an office for the Youth and Community Services team at Lambeth Council. 3Space renovated and repurposed the building for a mixture of creative, making, community use and workspace using a starting budget of just £100,000. This was used to secure a further £800,000 from partner tenants including high growth start-up businesses to bring the building into productive use. This type of unique activity—an interface between private business, civil society, start-ups, charities, culture, and creation—is unlike a typical market-led product and its uses wouldn’t be compatible with a new build corporate HQ. Nor, indeed, would it be able to cover the operating costs of a new build office.

The project generated significant social value: a recent analysis of International House showed that it delivered the same job numbers as a traditional new build office, with £413 per m2 of social value—15 times that of a new build (at £27 per m2). Repurposing and reuse can be low-cost, and if buildings like International House are retained in council ownership, they can significantly reduce the embodied carbon contribution, provide council with a steady income and deliver higher public value than more traditional approaches.

Measuring value

Regardless of the level of retrofit, these projects can’t be seen in isolation, particularly when numbers might demonstrate a less optimistic outlook. Existing buildings are embedded into urban fabrics with historical and community significance that need to be preserved and enhanced. Retrofits can help to ensure a just net zero transition, targeting those in disadvantaged contexts and with less access to more efficient, but less affordable, new buildings.

To be able to address some of those challenges, the way value is measured in the built environment needs to change. The economic and commercial value of retrofitting has to sit alongside its social and environmental impact. A nationwide retrofit programme, for example, could create space to upskill, future proof and create better quality jobs. Grosvenor states that upskilling the workforce to ‘retrofit UK’s historic buildings would lead to an additional £35 billion of output annually, supporting around 290,000 jobs’. In turn, building capacity in less advantaged communities can start to unlock one of the major barriers to retrofit on scale: the existing skills gap.

Other benefits of retrofit include enabling buildings to adapt to changing market demands. Shiny, Grade A buildings without a pre-let or user-led approach will most likely become a rarity outside of a handful of major UK cities, if at all. Occupier demand and rental growth have not kept up with build cost inflation, placing a viability squeeze on new development. New approaches should be piloted and better practice celebrated.

Lastly, the value of retrofits in strengthening the circular economy should not be forgotten, since they promote the reuse of materials and the sharing economy. They contribute to new ways of thinking that open space for systemic change and help to reduce resource depletion and associated environmental degradation. Moreover, they can start to recognise the global impact on communities and environments beyond the local influence of an asset.

Retrofit, yes

The building stock is variable and will require different approaches to transition successfully to net zero. Although a deep understanding of the whole-life carbon of an asset is paramount to comparing emissions and making informed decisions, it needs to go hand in hand with social impact and more comprehensive environmental degradation considerations.

Starting fresh can feel more comfortable, less complex, and easier to do, whereas adapting, solving compatibility issues, and changing the status quo can feel daunting and counterintuitive. Nonetheless, growth should not cost the planet and should be focused on creating regenerative places that work for the wellbeing of their local communities while being responsible towards their global impact.

The recent demolition refusal of Marks & Spencer’s Oxford Street store and the government’s efforts to decarbonise social housing are certainly positive steps in that direction. But we need to go bigger and faster. Retrofit has huge potential to deliver system change and decouple economic growth from resource depletion. These projects foster creativity and innovation, and ultimately lead to more diverse and attractive spaces commercially that also meet the socio-economic needs of the local community. Even so, we can only secure the potential environmental, social and commercial benefits of retrofit if we can deliver at scale. Masterplans have to start from the position that new development is not the first resort and urban regeneration needs to get closer to its meaning in nature: delivering places that adapt through regenerative and ecologically sound practices.

By Carolina Eboli and Chris Paddock