Breaking free from the comfort of carbon tunnel vision

The urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate the impacts of climate change cannot be overstated. In the fight against climate change, carbon emissions have rightfully taken centre stage, particularly those associated with the energy transition.

However, while carbon reduction is undoubtedly crucial, adopting a singular focus on carbon can lead to carbon tunnel vision, a narrow perspective that overlooks other vital environmental and social factors, such as biodiversity loss, ecosystem degradation, water scarcity, and social inequities.

In this article, we do not question the absolute need for wider buy-in from those who have yet to commit to fighting climate change and reducing carbon emissions; instead we explore the limitations of carbon tunnel vision of those who have already embarked on this journey, calling for a more holistic approach to climate action that considers the interconnectedness of environmental, social, and economic challenges to achieve a more just future.

Broadening the scope

Carbon emissions are undeniably a major contributor to climate change, but they represent just one piece of the complex puzzle. The United Nations states that we are living in a triple planetary crisis in which climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution are closely interlinked.

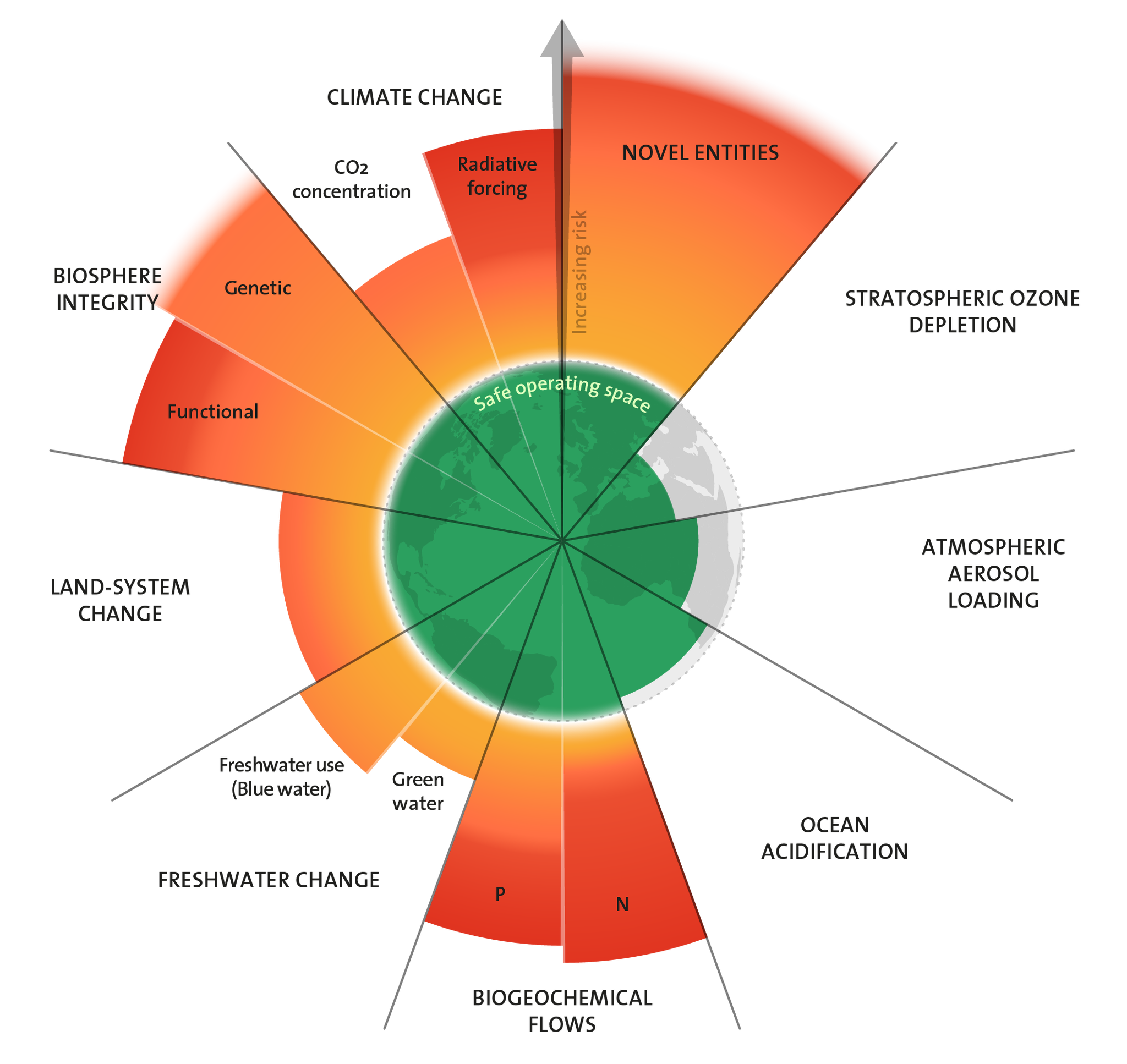

The planetary boundaries framework is useful because it provides us with a wider view of the level of challenge we face. It presents a set of nine planetary boundaries within which humanity can continue to develop and thrive for generations to come. When first introduced in 2009 by a group of scientists, there were still several gaps in the data available. In 2023, the framework was updated, and all boundaries have been measured, painting a bleak picture of our current situation: of the nine boundaries, six of them have transgressed the safe operating space – by far.

Planetary boundaries framework. Image credits Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, based on analysis in Richardson et al 2023.

Recognising the interplay between these environmental challenges is important to develop integrated solutions that address multiple dimensions of the crises we are facing. For example, material footprint is dangerously under-discussed but is one of the key issues contributing to the overshoot in the climate change, biosphere integrity and biogeochemical flow boundaries. We use three times more materials than we did half a decade ago, which continues to grow on average more than 2.3% per year.

Globally, ‘extraction and processing of material resources (fossil fuels, minerals, non-metallic minerals and biomass) account for over 55% of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) and 40% of particulate matter health-related impacts’. In addition, these practices add pressure to the built environment and create competition for land, which weakens climate resilience and biodiversity. More than 90% of global water stress and land-use-related biodiversity loss are due to raw material processing and extraction.

In a carbon-centric world, resource scarcity and associated environmental degradation end up missing from the bigger picture. While the energy transition might help to reduce carbon emissions from fossil fuel sources, it is speeding up the race for critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel. As a response, instead of focusing on reusing the minerals that have already been mined, we are looking for ways to further exploit existing sources or alternative mining options (for example seabed extractions, of which consequences are unknown).

Another example is the dysfunctional carbon offsetting systems that have been created. The scandal of the biggest certifier of carbon credits, in which more than 90% of its rainforest carbon offsets were proved to be worthless certainly played a significant role in the 61% shrink in the carbon offset market in 2023 – and demonstrates that we need better structures in place.

Carbon offsetting, similar to recycling, should only be the last resort. Finding new sources of critical minerals to deploy them in less carbon-intensive energy sources or planting trees to offset the carbon that should not be produced in the first place will not be enough to save us from the doom of not getting to net zero.

From a social perspective, carbon tunnel vision obscures the disproportionate impact of climate change on marginalised communities. Vulnerable populations and low-income communities bear the brunt of climate-related disasters and lack access to resources for adaptation and resilience. These communities face heightened vulnerability due to factors such as inadequate infrastructure, and limited access to healthcare.

Climate change also exacerbates existing social and economic inequalities, leading to health disparities, food insecurity, and displacement. In the near future, we will need to be prepared to deal with the consequences of climate refugees, which will not be too dissimilar to the current challenges and discussions around immigration due to wars. Lastly, marginalised communities are frequently excluded from decision-making processes, perpetuating a cycle of vulnerability and inequity.

The recent huge disaster in the South of Brazil, where extreme rainfall (500 to 700mm in five days, the equivalent of a whole year of rain) affected 90% of the territory and 94.3% of all economic activity of Rio Grande do Sul State, paints a picture of the scale of the threat we all face: 157 deaths; 600,000 displaced; and 2,336 million people affected by the wide destruction. Known for being an area of intense agricultural and industrial production including rice, soy and wheat, the economic impacts of their loss will be reflected in food prices and inflation not only in Brazil but internationally. In the aftermath, again, disadvantaged communities will be the ones struggling to cope.

Besides dealing with the knock-on effects of climate disasters elsewhere, we need to think more about the negative social impact beyond our borders which results from our behaviours and choices. For example, the United Kingdom is one of the most important investment hubs for the global mining industry and most of the world’s biggest mining companies are incorporated here. Chile is responsible for producing around 40% of the world’s copper and has the world’s largest copper mine ‘Escondida’ – majority owned and operated by companies listed on the London Stock Exchange.

We fail to consider the impact extractive and pollutant activities create in those local communities, which tend to be in conflict areas or places with weaker governments. Mining activities typically do not provide good quality jobs for local workers and highly skilled jobs are often taken by those not from the region or community where the mine is located.

The social and environmental impacts of renewable energy infrastructure, the inequities inherent in carbon offset markets, the unintended consequences of certain technologies and processes, and the more frequent and intense climate disasters highlight the limitations of relying solely on carbon emissions to define our strategies, policies, and initiatives. A nuanced approach that combines innovation with behavioural change and systemic reforms is necessary for tackling the multiple crises we are facing.

The way forward

Circular Economy

The high demand for materials cannot be seen as a free pass for continuously seeing raw materials as infinite. The global energy transition must be coupled with a regenerative economy, where critical minerals can be reused over and over again.

Circular Economy is the fundamental step needed towards decarbonising and building economic and environmental resilience, which needs to be complemented by a shift in our consumption patterns to reduce demand for both energy and virgin minerals. This would reduce the need for new extraction, increase the recovery of valuable materials and minimise waste.

Innovative approaches in the circular economy already include advanced recycling technologies like the recent hope that cement from demolished concrete buildings can be finally recycled, material passports that track the composition and lifecycle of products such as Madaster, and material exchange providers, such as SalvoWeb, that help to enhance material reuse. However, even though the construction sector has been making progress, circularity must be extended to other sectors too.

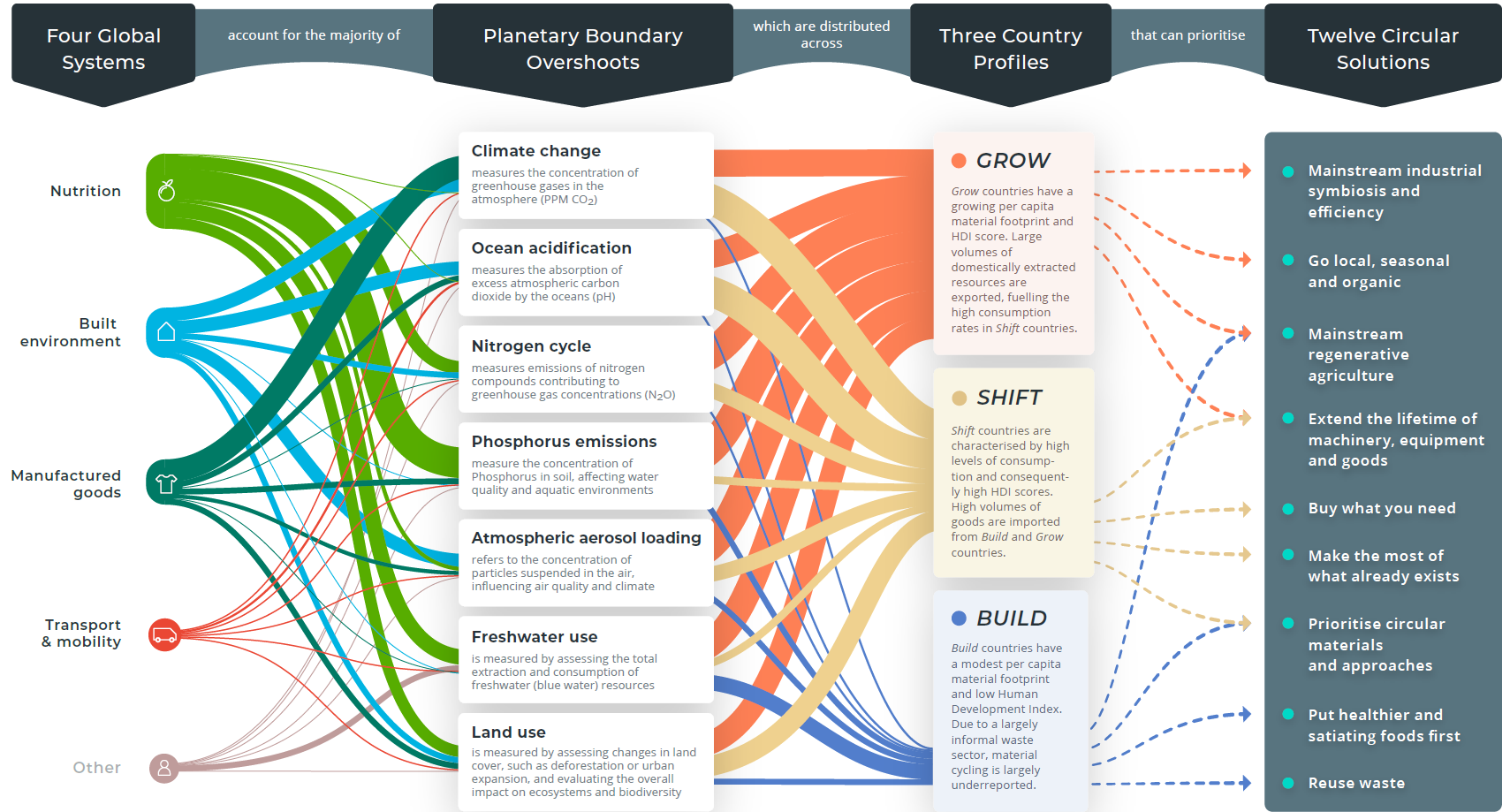

In Circle Economy’s latest Circularity Gap Report (2024), they identify four major global systems responsible for most planetary overshoots: food, transport, built environment and manufacturing. They suggest three different country profiles and twelve circular solutions each country profile should prioritise. While different contexts and scales will require tailored approaches, these circular solutions are a starting point to address some of the challenges mentioned.

In London, pilot initiatives such as the Loop in Hackney Wick – a circular economy hub to help local businesses expand their operations, foster synergies between them and trial new circular processes and products are important to demonstrate action and unlock investment appetite for physical circular hubs and neighbourhoods that are not solely focused on construction.

Nature-based solutions and biomimicry

Forests, wetlands, and oceans play a crucial role in regulating the climate, enhancing biodiversity, and supporting human livelihoods. Nature-based solutions (NbS) can create strategies for addressing societal challenges by leveraging natural processes and ecosystems. These solutions involve the protection, sustainable management, and restoration of natural or modified ecosystems to provide both human wellbeing and biodiversity benefits. They aim to harness the power of nature to tackle issues such as climate change, water and food security, human health, and disaster risk management.

NbS also emphasise the importance of working with nature to create sustainable and resilient ecosystems that can withstand environmental changes and provide essential services. For instance, restoring wetlands can improve water quality, sequester carbon, and reduce flood risks, while reforestation projects can enhance carbon sequestration, protect biodiversity, and improve local climates.

Several NbS are based on ancestral knowledge and require low technology. Constructed wetlands or reedbeds, for example, are a decentralised alternative for wastewater treatment that requires low maintenance and energy, and they can be integrated into the surrounding landscape.

In Ashbourne, Severn Trent Water implemented the first full-scale application of constructed wetland technology for a full treatment of municipal sewage, serving a population of approximately 900 people. In Derbyshire, a pioneering water treatment facility using floating wetlands to pre-treat water naturally is being implemented as part of a £566m Green Recovery programme that will help secure water supplies for the future.

Alongside NbS, replicating nature’s designs and processes to innovate in human-made systems and technologies (biomimicry) can be a powerful tool to promote circularity. For example, MadLeap created a technology to simulate the natural process anaerobic microbes go through to break organic waste, capturing the biogas produced as by-product for other uses on site. The leftover food waste is turned into digestate, a nutrient-rich natural fertilizer that supports food production, creating a fully closed loop.

Working with existing natural systems to enhance their functions and benefits and improve ecosystem resilience, and learning from nature to create new systems or products to achieve innovative, sustainable, and efficient solutions are crucial to help us shift towards more regenerative practices.

Just transition

Regardless of the climate action, all initiatives must prioritise equity, inclusion, and community engagement to ensure that the burdens and benefits of climate mitigation and adaptation are distributed fairly across all populations, particularly marginalised and vulnerable groups. Empowering communities and amplifying diverse voices and experiences to take ownership of climate action is essential for creating sustainable change.

Climate Citizen Assemblies are a good way to involve local communities in decision-making processes related to climate action. These assemblies can provide diverse perspectives, foster democratic engagement, and ensure that climate policies reflect the needs and values of the people most affected by them. In 2020, Climate Assembly UK (United Kingdom) brought together a diverse group of over 100 people to discuss how the UK should meet its net zero target.

Grassroots initiatives that address local environmental and social challenges can also demonstrate the power of community-driven solutions. Empowering communities to take control of their energy sources through cooperatives can drive both social equity and environmental benefits. These cooperatives can install and manage renewable energy systems, ensuring that profits and benefits stay within the community. This model promotes local job creation, energy independence, and equitable access to clean energy. Community Energy London has supported the creation of several groups and projects following that model.

A just transition emphasises the importance of ensuring that the shift towards a low-carbon economy does not leave anyone behind. This involves creating opportunities for green jobs, providing education, and training for new skills, and ensuring that policies are inclusive and equitable. By focusing on social justice and community resilience, we can leverage the climatic transition and challenges to deliver co-benefits for both the people and the planet.

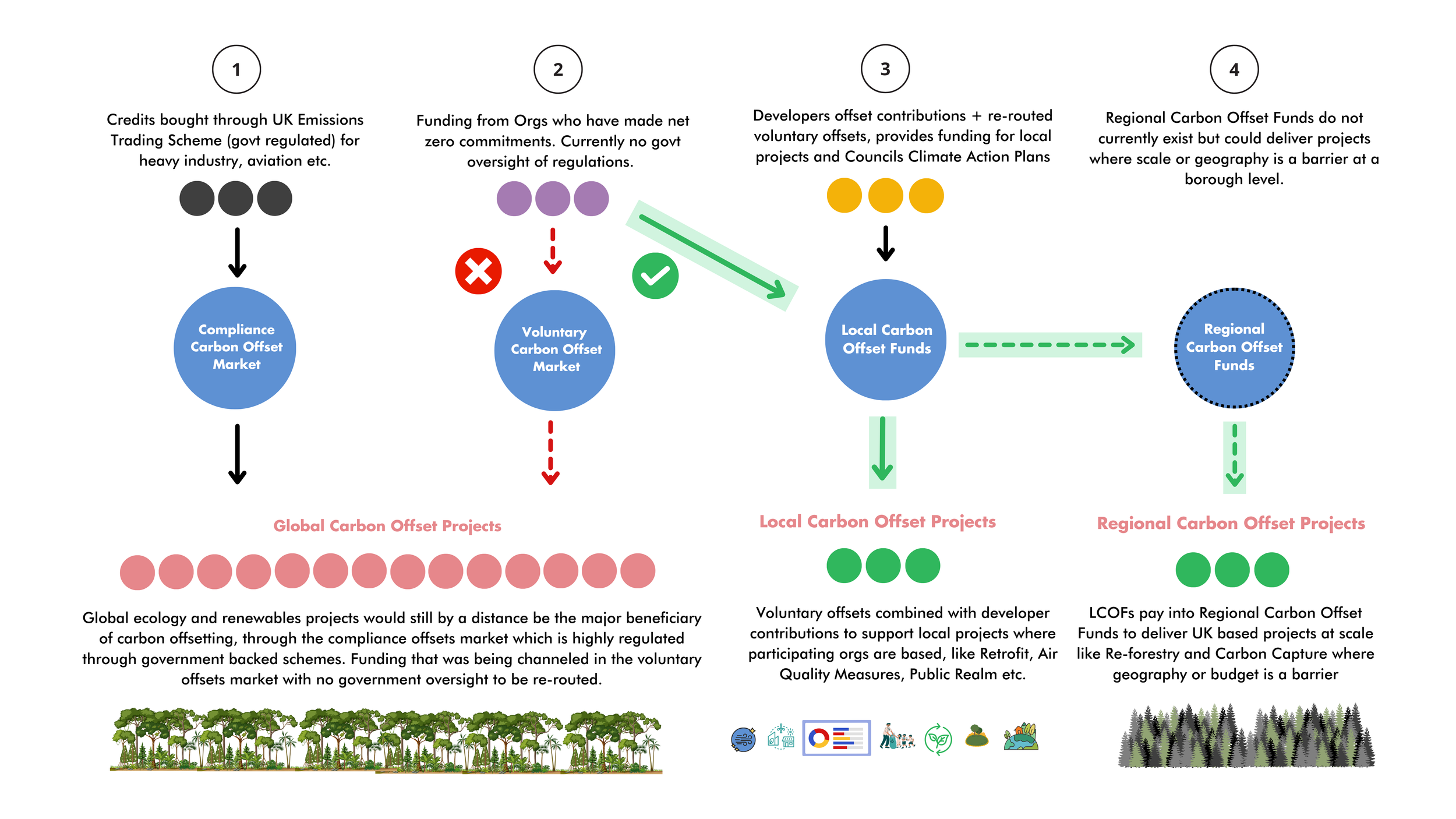

Local Carbon Offset Funds (LCOF)

While we transition to net zero, we will still need interim mechanisms such as carbon offsetting to help us in the near and medium future. However, localising the impact of offsetting can be a more meaningful solution which could help to support not only positive environmental outcomes but also deliver a wider range of social and economic value and public health benefits.

The White House has recently published Principles for Responsible Participation in Voluntary Carbon Markets to address the credibility challenges this market faces. One of them highlights the need to prioritise reductions within local value chains. Creating local versions of carbon offset funds can pave the way for programmes that offer direct environmental benefits while simultaneously supporting local economies and enhancing social equity.

By focusing on local initiatives, these programs can create tangible impacts within communities, fostering a sense of ownership and immediate benefits that larger, more abstract global initiatives might lack. Together with meaningful engagement and education strategies to promote broader participation and support, these initiatives could involve community-based projects such as reforestation, renewable energy installations, and energy efficiency improvements. Furthermore, LCOFs could help to establish transparent and robust measurement and verification standards to restore the credibility and impact of carbon offsetting.

Alternative framework for Local Carbon Offset Funds. Image credit: REDO

Final reflections

The way forward is not entirely new. We already possess the principles necessary to tackle these challenges and achieve better outcomes. The true task lies in transforming and embedding these principles into action at the scale and pace required. This transformation must occur with the premise that climate solutions cannot be divorced from social and economic contexts. Sustainable development that considers human wellbeing, livelihoods, and economic equity is essential for building resilience to the inevitable impacts of climate change. To achieve this, we need bespoke and robust data and measurement frameworks to track progress and to tailor future approaches for greater social and environmental impact. Additionally, regulatory frameworks must prioritise environmental justice, social equity, and ecosystem integrity.

While the journey ahead is demanding, we can amplify current efforts by broadening our perspective beyond a carbon vision, which can open the door to more creative solutions to unlock complex, interconnected problems and deliver far greater benefits and a truly just transition.

– By Carolina Eboli. Contact Carolina to learn more about sustainable development and embedding circular economy principles.