Are high streets meeting Londoners’ needs?

For the first time ever, London is hosting London Data Week, a festival of events and exhibitions for people to learn and talk about how data can influence London for the better. At PRD we rely extensively on high-quality data to inform the work we do, so to contribute to the discussion, we’ll be publishing a series of journal entries to share our experiences with and ambitions for data in London and beyond.

London has more than 600 high streets and town centres with enormous diversity of size, activities, catchments, and roles in the city’s economy. One common thread across most of these places is that they tend to be dominated by retail—but retail is no longer the draw it once was. As the narrative often goes, people are choosing to prioritise having ‘experiences’ in person (e.g. a meal out with friends, going to the cinema) over buying ‘things’, which can often be ordered online.

At the same time, Covid-19 lockdowns put the spotlight on the services and workers essential to daily life: fresh food and supermarkets, pharmacies, health services, hardware stores, newsagents, and more.

High streets need to move beyond their retail focus if they are to adapt to changing habits and needs. Recasting the role of high streets as places that meet essential wellbeing and social needs is one route to take. Through our ongoing work with the GLA’s High Streets Data Service, we are attempting to unpick what exactly this new role entails.

Foundational goods & services

Recently, a consortium of academics has been developing the concept of ‘foundational economy’ as a new way of thinking about what the focal point for economic policy should be. The foundational economy relates to basic goods and services that meet every day needs: care, health, housing, food, education, and utilities. This is a useful starting point for understanding which goods and services people should be able to get from their local high street as standard.

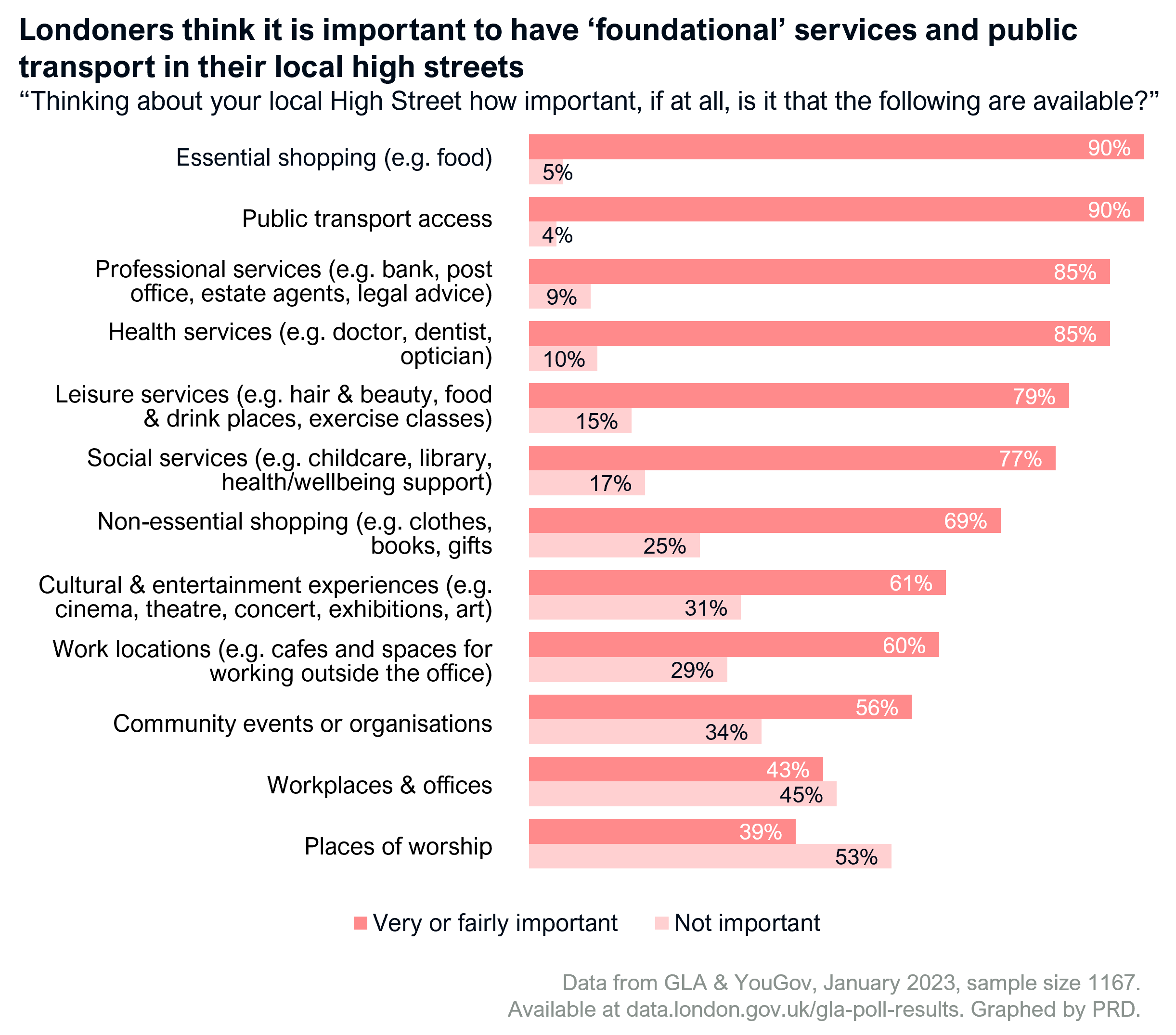

Other considerations come from polling. For example, nationwide research in 2018 saw banks, post offices, and pharmacies, restaurants, and clothes shops in the top three places for necessary high street services. In London in January 2023, the GLA asked Londoners via YouGov about the most important features for high streets, with essential shopping, public transport access, professional and health services, and leisure in the top five.

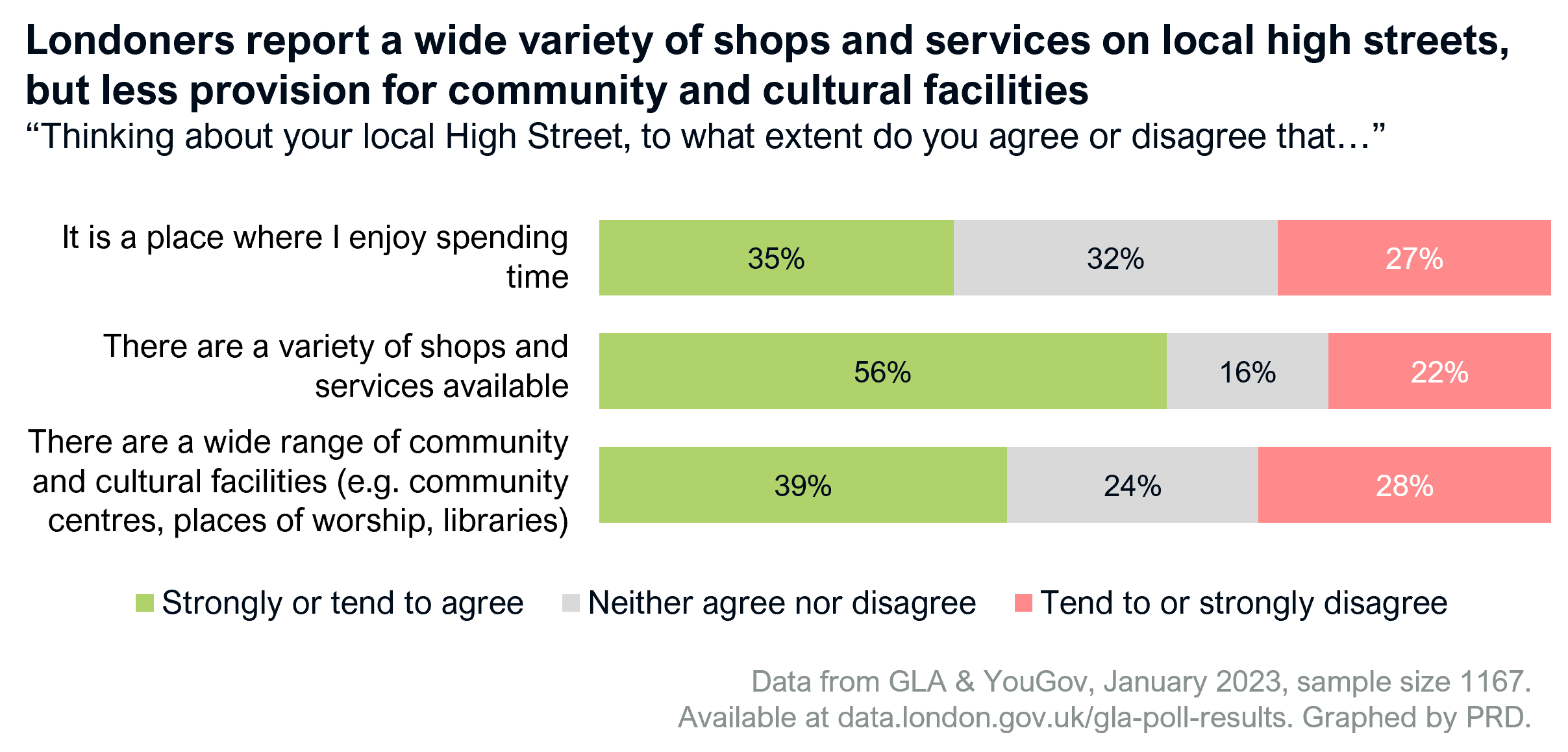

They also asked about general perceptions of the high street. 56% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their local high street had a variety of shops and services, but only 39% agreed or strongly agreed that the high street had a wide range of cultural and community facilities.

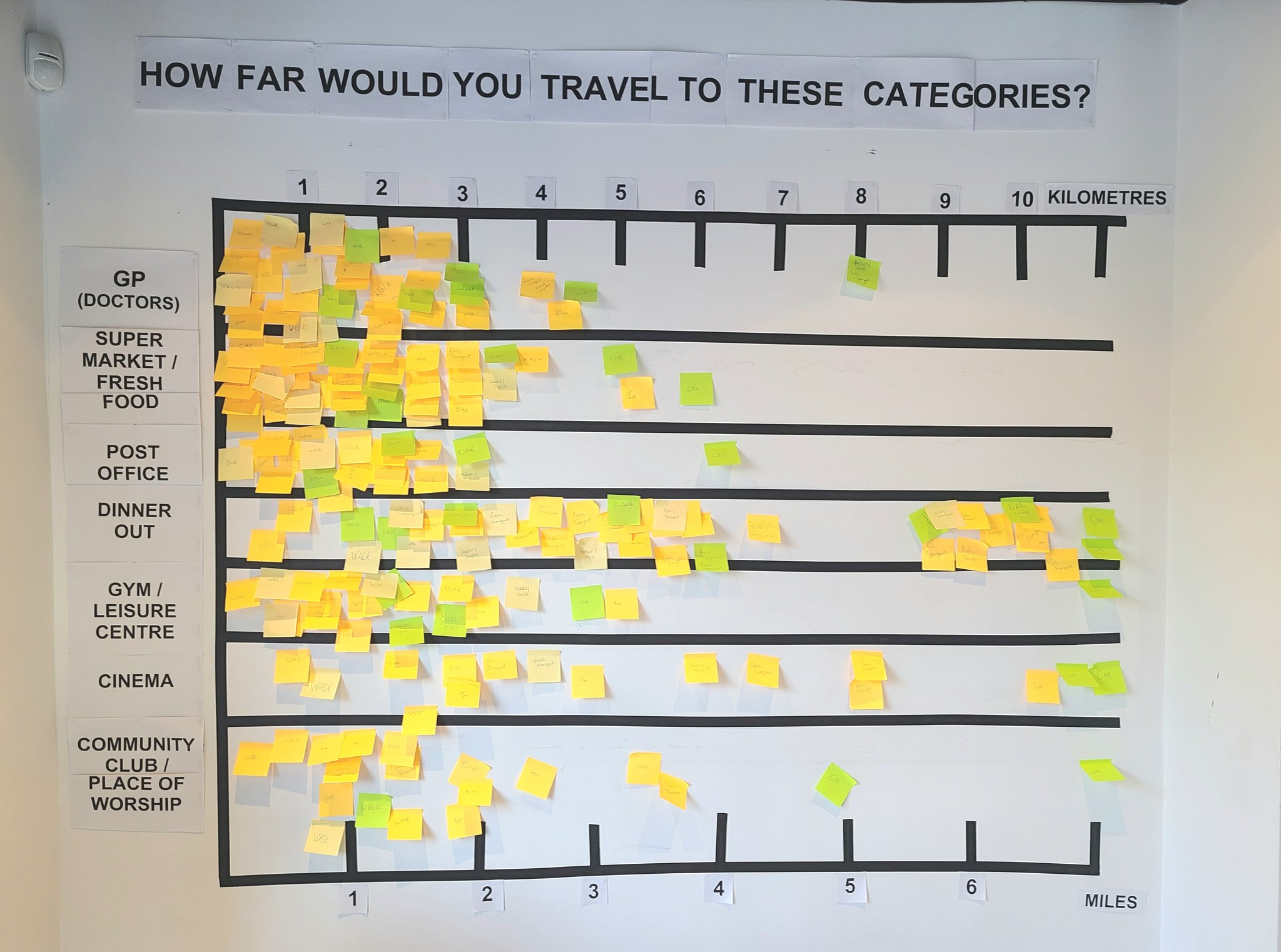

Much more informally, at the GLA’s Data in the High Streets pop-up in Shoreditch High Street during London Data Week, a crowdsourced data visualisation project found that many people prefer to travel short distances, ideally by walking (as noted on the sticky notes in the photo below), for basics like GP surgeries, fresh food, and leisure centres.

London’s high streets & local need

Using the research and ideas noted above, we’ve developed categories of foundational goods and services that people might expect to find in high streets:

Food

- Supermarkets (including chains such as Lidl, Sainsbury’s, etc as well as independents)

- Convenience stores/convenience food and drink

- Fresh food basics (e.g. butchers, bakeries, greengrocers)

Health

- GPs/health centres

- Pharmacists

- Opticians

- Dentists

Services

- Post office

- Banks

- Childcare/nursery

- Libraries

Through the High Streets Data Service, subscribers have access to Experian ShopPoint information on thousands of high street units throughout London: their occupiers, use categories (e.g. charity shop, pet store, cinema), ownership (chain vs not a chain)—or whether the unit is vacant altogether. We are using this data to test how we can apply these categories of foundational high street goods and services and understand service provision in different areas.

We are still exploring the Experian data, but one interesting early finding is that London’s designated town centres generally appear to provide a basic level of choice for fresh food basics (grocers etc) and convenience stores, but are very lacking in options for health centres and childcare. Only 19% of town centres have at least two health centres (51% have at least one, not shown in the graph below) and only 12% have at least two nurseries (32% have at least one).

n.b. dentists and libraries not included in graph as they are not listed in the Experian data

Note that this is only a very basic assessment, based on having at least two of each category in a town centre (other than post offices, because even the largest high streets/town centres rarely have more than one). It does not account for the quality or accessibility of the amenities/services or the range or affordability of their goods. But it is a starting point for discussion and further on-the-ground investigation.

Regarding the data, the lack of GPs and childcare might not seem important—after all, GP and childcare facilities are often located in residential areas rather than high streets. But with around 12% of GP wait times pushing beyond two weeks (Nov 2022 data) and some parents seeking to secure a place at a nursery before their child is even born, arguably London needs more of these services in the right places. High streets are ideal because they are often well-connected by different modes of transport, they allow people to link visits to core services with other errands, and there is more space that can be leased or converted. Of course, not all vacant units may be suitable, and there are still major challenges with an insufficient number of NHS GPs and childcare professionals to meet demand, costs of running nurseries, and costs of paying for nurseries that also need to be tackled.[1]

When reviewed against data on local demographics—such as areas where large proportions of people are in ill health or there is projected to be a growth in the number of young children—we can start to understand which neighbourhoods might have a particular need for these types of services and plan for provision.

This is just one angle. Another might be to identify areas where people are more likely to face isolation and review the social, cultural, and leisure amenities (e.g. community centres, bowling alleys, leisure centres) available in nearby high streets. If service provision is good on paper, a priority could be to understand people’s barriers to accessing those services and enable them to do so; if provision is poor, a priority could be to learn what would help people connect and seek to deliver that locally.

Final thoughts

This is all a work in progress and there is plenty more to investigate. In coming weeks we’ll be reviewing potential areas of focus with the GLA and Data Service subscribers. Although we are using a specific dataset for this research, the methodology we are developing could be applied to other ‘points of interest’ type data (e.g. from Ordnance Survey or other data suppliers). We are excited about the opportunities this presents, and would welcome connecting with others interested in this line of work.

– By Amanda Robinson. Contact us if you are interested in this work or want to learn more about how it might apply to your own local high streets and town centres.

—-

[1] See, for example:

- British Medical Association, Jun 2023. “Pressures in general practice data analysis” https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/pressures/pressures-in-general-practice-data-analysis

- Royal College of General Practitioners, Jul 2022. “Brief: GP shortages in England” https://www.rcgp.org.uk/getmedia/3613990d-2da8-458a-b812-ed2cf6d600a6/RCGP-Brief_GP-Shortages-in-England.pdf

- Kate Wills, Evening Standard, Sep 2022. “Soaring nursery costs, recruitment issues and chronic underfunding — inside London’s childcare crisis” https://archive.ph/mdQgQ

- Aditya Chakrabortty, The Guardian, Apr 2023. “Disappearing schools, families forced out – and we call this progress” https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/apr/13/city-without-children-dystopia-new-reality-london

- Sally Weale, The Guardian, Jul 2022. “‘It feels like a sinking ship’: inside Britain’s struggling nurseries” https://www.theguardian.com/money/2022/jul/21/it-feels-like-a-sinking-ship-inside-britains-struggling-nurseries

- Sarah Marsh & Denis Campbell, The Guardian, May 2023. “Patients paying £550 an hour to see private GPs amid NHS frustrations” https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/may/19/patients-paying-550-an-hour-to-see-private-gps-amid-nhs-frustrations

- Anna Davis, Evening Standard, Jul 2023. “Finding staff to back Government 30 hours childcare pledge is tough, says minister” https://archive.ph/5UV1x